Holocaust

Holocaust/Shoah was the systematic, state-sponsored persecution and murder of approximately 11 million people by the Nazi regime in Germany and its collaborators during the Second World War.

Holocaust/Shoah

In 1933, when Nazis came to power, the Jewish population of Europe was over nine million. Soon after they came to power, under Hitler’s leadership guided by racist ideas and organizing the police power to enforce Nazi policies, they adopted measures to exclude Jews whom they considered to be the “inferior race” that posed threat to the German race (Volk), from German economic, social and cultural life and forced them to emigrate.

Holocaust/Shoah was the systematic, state-sponsored persecution and murder of approximately 11 million people by the Nazi regime in Germany and its collaborators during the Second World War.

In 1933, when Nazis came to power, the Jewish population of Europe was over nine million. Soon after they came to power, under Hitler’s leadership guided by racist ideas and organizing the police power to enforce Nazi policies, they adopted measures to exclude Jews whom they considered to be the “inferior race” that posed threat to the German race (Volk), from German economic, social and cultural life and forced them to emigrate. Jewish businesses were boycotted. The government enacted a law to dismiss Jews from being employed in civil service. (1933) Similar laws also passed that affected Jewish doctors and lawyers. It was forbidden for Jewish doctors to treat non-Jews, while Jewish lawyers were not permitted to practice law.

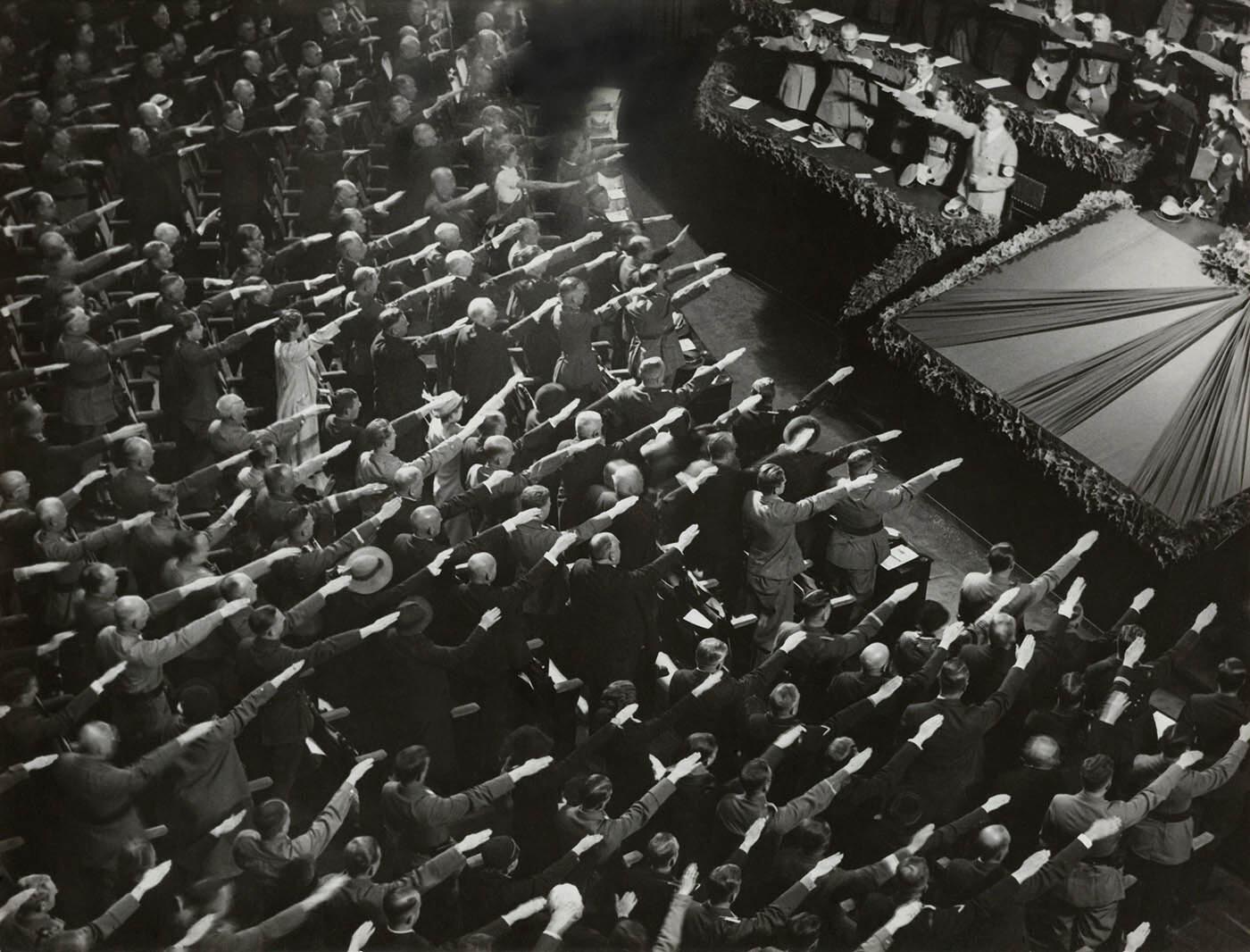

At the annual rally of 1935 of the Nazi party, in Nuremberg, the Nazis accepted laws institutionalizing racial theories employed in Nazi ideology. These laws excluded German Jews from Reich citizenship and Jews were prohibited from marrying or having children with people of German blood in order to protect and develop “pure German race”. Later, this law was also extended to other groups such as Roma (Gypsies) or the people of color.

On the night of November 9-10, 1938, known as the Kristallnacht (literally, Crystal Night in English and also known as the Night of Broken Glass), violence against Jews spread across the country. Over 250 synagogues were burnt and Jewish businesses were looted. Following the violent attacks, around 30 thousand Jewish men were arrested and sent to concentration camps as well as Jewish women who were arrested and sent to jails. In the aftermath of the Kristallnacht, Jews were systematically excluded from all aspects of public life in Germany, including public schools and businesses.

The Nazis and collaborators employed written records such as Jewish communities’ own records, tax documents, police records as well as local knowledge in order to locate and identify Jews to round up and kill.

During the Second World War, the Nazi regime had carried out the most brutal plan of their ill-guided ideology and begun implementing the stage they called as the “final solution to the Jewish question”. By the end of the war in 1945, nearly two-thirds of Jewish population in Europe were exterminated.

Together with the persecution of approximately 6 million Jews, the Nazis also persecuted Roma people (Gypsies), people with mental or physical disabilities as well as other groups targeted on political, ideological and behavioural grounds which ended up with the murder of 11 million people.

The Nazi concentration camps, also known as death camps were at the heart of the system of repression and destruction of political opponents of the Nazi state as well as people who were considered to threat German Volk that would unite under Hitler’s racist and violent ideology. Throughout the war, the purpose of the camps evolved from imprisonment towards forced labour, torture and murder. Together with concentration and extermination camps, ghettos where Jews were forced to live and work, and Einsatzgruppen, namely the operational groups made up of Nazi SS units (Schutzstaffel, or Protection Squadron which is a major paramilitary organization of Nazi Germany) and police were all means of a multi-staged murder of the “enemies of the Nazi state”.

After the war ended with Germany’s defeat, high-ranking Nazi officials were tried for the crimes of Nazi government, including the Holocaust, before International Military Tribunal. The crimes examined before the court were crimes against peace, war crimes, crimes against humanity and conspiracy to commit any of the foregoing crimes. In all, 199 defendants were tried at Nuremberg, 161 were convicted and 37 were sentenced to death. Yet, the Nazis’ highest authority responsible for the Holocaust, Adolf Hitler and some of his close aides were missing at the trials.

Türkiye During The Holocaust Shoah

Türkiye is firmly dedicated to the legacy of multi-faith tolerance and cultural pluralism inherited from the Ottoman Empire. Türkiye, where Antisemitism has always been devoid of any social base, has been a safe haven for Jews throughout the centuries seeking refuge from persecution.

Türkiye is firmly dedicated to the legacy of multi-faith tolerance and cultural pluralism inherited from the Ottoman Empire. Türkiye, where Antisemitism has always been devoid of any social base, has been a safe haven for Jews throughout the centuries seeking refuge from persecution.

The Turkish people welcomed numerous Jews fleeing the Holocaust/Shoah with open arms. Prominent German and Austrian scientists, most of whom were Jewish, were offered shelter in Türkiye and continued their academic careers at Turkish universities.

Türkiye was neither the victim nor the perpetrator/collaborator of Holocaust. On the other hand, the Turkish government and diplomats abroad did not remain idle towards this tragedy. Courageous Turkish diplomats serving in Europe during the Second World War were instrumental in saving the lives of hundreds of Jews. Selahattin Ülkümen, the then Consul General of Türkiye in Rhodes, who managed to save numerous Jews from deportation to Auschwitz July 1944, was among these who was recognized by Yad Vashem as Righteous among the Nations.

In line with this understanding, Türkiye was the main sponsor of the first United Nations (UN) Resolution defining Antisemitism as a human rights violation.

Türkiye also co-sponsored the UN resolution in 2005, designating January 27, the day that Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp were liberated, as the International Holocaust Remembrance Day. Since 2011, on every January 27, a ceremony with high ranking political participation has been held for the victims of the Holocaust, to not only remember and honour the memories of victims, but also to raise awareness for the prevention of such crimes in the future. With a ceremony and via the press release published every year by the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, it is emphasized that lessons should be derived from the Holocaust and it is essential to resolutely fight against all hate-based acts including Antisemitism, racism, xenophobia and Islamophobia.

Since 2008, Türkiye has been participating in the meeting and activities of the “International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA)” as an observer country, with a delegation comprising members of the Turkish Jewish Community and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Türkiye shares the values of IHRA and gives its support to researching the Holocaust and teaching this crime adequately to younger generations in order to prevent its recurrence.

Türkiye also commemorates the victims of Struma incident, known as the “Struma Disaster”, every year with ceremonies hosted by the Governor of Istanbul. Struma vessel, carrying Jewish people fleeing from the cruelty of Nazis and their allies was torpedoed by a Soviet submarine on February 24, 1942, resulting in the deaths of its 768 passengers. Every year, Ministry of Foreign Affairs publishes a press release commemorating the people who lost their lives in the Struma disaster.

An Intellectual Exodus: Jewish Academics Who Found a Safe Haven in Türkiye in the 1930s

As a country building a modern society and state in the 1930s, Türkiye attracted many Jewish academics and intellectuals fleeing the Nazi regime from 1933 on. Such transformation also required a revision, or to put it more thoroughly, a formation from scratch of the higher education system.

As a country building a modern society and state in the 1930s, Türkiye attracted many Jewish academics and intellectuals fleeing the Nazi regime from 1933 on. Such transformation also required a revision, or to put it more thoroughly, a formation from scratch of the higher education system (Reisman, Geiringer, 1-2). Within the framework of a reform programme called “Üniversite Reformu,” Mustafa Kemal Atatürk led the country to conduct a profound transformation, partly thanks to the contributions of these Jewish-German emigrés. The persecution towards the Jews in Germany and the “Üniversite Reformu” in Türkiye coincided, paving the way for a combination that had a crucial impact both on Turkish and global cultural/scientific development and the existence of Jewish intellectual heritage (Reisman, Geiringer, 2; Şimşir, 102). Reşit Galip, who was the Turkish Minister of National Education at the time, designated this process as “a new Renaissance” (Şimşir, 109).

Eventually Türkiye hosted hundreds of Jewish intellectuals during this term (Reisman, Geiringer, 3). The official invitations were extended to almost three hundred (mostly) Jewish scientists and professionals from Germany and Austria. This number continued to increase to include families, assistants, and staff, numbering some one thousand individuals in all. Once Turkish visas and offers for employment were extended, the Reichsregierung (German Government) could no longer avoid permission to travel (Aksakal). These included three professors who were saved from concentration camps through Turkish diplomatic efforts (Reisman, Geiringer, 5; Şimşir, 110; Reisman, Türkiye Modernization, 33). Arnold Reisman, a prominent scholar who has comprehensive studies on this period, emphasizes that Türkiye's initiative “provided them safe haven from annihilation when no other country would (…)” (Reisman, Geiringer, 13). One of the emigrés, Fritz Neumark, expresses himself in this regard as below:

For us, being able to work there, thus enjoying the possibility to do useful work and even, for most of us, to exist is … the foundation of our gratefulness to [Türkiye] (Şen, 118)

In his foreword of the book called Ay Yıldız Altında Sürgün (Exile Under the Star and Crescent, originally published in German as Exil unter Halbmond und Stern), President of Germany Frank-Walter Steinmeier, quoting Neumark’s abovementioned statement, also underlines the significance of this period of refuge for the relations between two countries today (Şen, 7-9).

There are also many accounts that describe their living conditions in Türkiye, such as of Ernst Hirsch, who spent a considerable lifetime in Türkiye and made significant contributions to the Turkish legal structure. In his memoir, Hirsch describes the professional and living conditions in Türkiye as “better than good” by making a comparison with the other potential European destinations of refuge (Şimşir, 113; Reisman, Türkiye’s Modernization, 36).

Türkiye’s efforts to protect these people did not end upon their arrival but continued during their stay, too. As a part of the Nazi efforts to exert pressure on the Turkish government to deport Jewish intellectuals and replace them with the “Aryan” academics, the Reich Ministry of Education sent a senior government official (Oberregierrungsrat), Herbert Scurla, to Türkiye. Scurla conducted two inspection visits to Türkiye in 1937 and 1939 (Şen, 24). This was clearly related to the Nazi designs to gain an upper hand in European governments’ position in the emerging political climate. That said, his mission was to monitor German intellectual refugees' activities and classify them according to their races and political views. The results of these two visits were reflected in the infamous report referred to as Scurla Report (Reisman, Türkiye's Modernization, 34). However, the Nazi administration’s bid for convincing the Turkish government to suppress the Jewish and regime’s political opponents proved to be a failure. Türkiye's upright stance has never allowed these people to be mistreated (Şen; 7, 14, 28, 110, 112, 113, 214). In his notes on the report, Fritz Neumark gives his “deepest” thanks to the Turkish government and his Turkish colleagues for taking their sides against Scurla’s intentions (Şen, 118).

In contrast with Türkiye's welcoming approach to these Jewish intellectuals, during the period in question, the US had strict immigration laws and anti-Semitic biases at its universities, which deprived these Jewish academics of the opportunity to work there. Foremost US universities such as Harvard, Yale, Brown, and Princeton had been free of Jewish scholars during the 1930s and 1940s. (Reisman, Türkiye's Modernization, 312). One of these Jewish intellectuals, Hilda Geiringer, is a representative example in this case. Although she, as one of the pioneers of applied mathematics as well as many other scientific fields, first attempted to find a job in the US, she was not able to do so due to the anti-Semitic and sexist environment in the country at the time. Even Albert Einstein’s reference was not good enough to make her find a job (Reisman, Geiringer, 1). Therefore, initiators of this “exodus,” such as Philipp Schwartz and Albert Einstein, preferred contacting Türkiye rather than the US. Einstein, with a letter that is addressed to İsmet Bey (İnönü), then the prime minister of Republic of Türkiye, appealed for permission that “forty professors and doctors from Germany to continue their scientific and medical work in Türkiye” (Reisman, Shoah, 81).

In return for Türkiye's welcoming approach, these Jewish intellectuals greatly strengthened the foundation of Türkiye's scientific, academic, and cultural tradition in many different fields, stretching from botanic and bacteriology to sociology and law to music and architecture. Moreover, Türkiye played a role in keeping this “intellectual capital” safe and sound for the future development of Western science and technology, since some of these Jewish intellectuals later pursued their academic aspirations in the European and US universities after World War II and made a remarkable contribution in this context. On the other hand, some of them devoted their lives to improving the Turkish academic framework. They continued to work in Türkiye even after the War. As a matter of fact, at the expense of Nazi resentment, Türkiye granted citizenship to some, starting with Prof. Rudolph Nissen (Şimşir, 130). As an extension of the 1930s, Türkiye's endeavor continued well into World War II, with many Jews finding refuge in Türkiye (Reisman, Shoah, 67-73).

Türkiye And The Jewish Community During The Second World War

After the conflicts of the First World War had ended with the Armistice of Mudros for the Ottoman Empire, the victorious states would return to managing their interests in the Near (Middle) East as it was referred to in that period.

After the conflicts of the First World War had ended with the Armistice of Mudros for the Ottoman Empire, the victorious states would return to managing their interests in the Near (Middle) East as it was referred to in that period. The period from October 30, 1918, when the armistice was reached until July 24, 1923, when Lausanne Peace Treaty was signed went down in world history as a period full of wars of partition and invasions on Türkiye and the Middle East.

When we reach the end of this crossroads, it is seen that the following issues were included in the petition submitted by fifty Jewish citizens from İstanbul, Edirne, İzmir, Aydın, Manisa, Bursa and Çanakkale provinces, most of whom were former MPs, professors, bank managers, finance inspectors, doctors, pharmacists, lawyers, publishers, merchants and real estate agents, to İsmet Pasha (İnönü), the head of the delegation who would depart from Istanbul to attend the Peace Conference to be convened in Lausanne on November 10 1922.

(I) The Jews shall always remember that the Turks embraced and protected them five hundred years ago, with the purest tolerance and in the spirit of humanity, without any ulterior motives.

(II) Acting chivalrously regardless of race and religion, Türkiye did not shy away from receiving the oppressed from all countries.

(III) Turks granted the Jews all freedoms to lead religious and private community without any request.

(IV) For five hundred years, Jews safely lived in Türkiye and in that time had never complained about the government.

(V) When there was an attack against the Jewish community in the country, the Turkish governments defended the Jews in the most energetic and praiseworthy manner.

(VI) Dramatic incidents that frequently erupted between the Jews and Arabs after the disintegration of Palestine from Türkiye were not the case during Turkish rule.

(VII) The only way to re-establish peace in Palestine and to cease current hostilities between the two elements in the region is to entrust the Mandate of Palestine to Türkiye.

(VIII) Following the custom of governing these two elements in a competent and humane manner, Türkiye shall, undoubtedly, rebuild harmony on those territories for the community in Palestine and the good of all humankind.

The document shedding light on the feelings, thoughts and desires of the Turkish Jews in the wake of The First World War and our War of Independence, is the proof of Jews’ confidence in the Turkish government as they asked for Turkish mandate in the region to prevent the turmoil and conflicts and to establish peace and stability in Palestine that was occupied after 1918. Although Britain's military occupation of Palestine after the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I and the Mandate for Palestine was principally granted to Britain at the Supreme War Council meeting held in San Remo on April 25, 1920, the fact that Turkish Jews wished the Mandate for Palestine to be granted to our country is a remarkable historical event that reveals the confidence in Türkiye for re-establishing order in the region. This wish once again corroborates the equity and justice of the traditional Ottoman community system.

During the Second World War, Türkiye’s efforts to protect and save the lives of Turkish Jews abroad and its achievements in this field are narrated in the book, Turkish Jews, penned by the retired Ambassador Bilal Şimşir published in two volumes in 2009. The book unravels the activities of our diplomats, who held office in Paris/Vichy Embassy and our Consulate General in Paris and Marseilles between 1942 and 1944 and took Turkish Jews under their wings.

Despite all the unfavourable atmosphere and circumstances between 1939 and 1945, Türkiye did not refrain from supporting non-citizen Jews as much as it could within the limits of our legislation as it did for the Jewish citizens. Transit pass was made easier for refugees from Central and Eastern Europe, who crossed Romania by sea and wished to go to Palestine. Our government allocated special wagons of the State Railways for these people to travel between Haydarpaşa and Aleppo, despite the food shortage and scarcity of our transportation vehicles. In addition, during the transit, Türkiye did not shy away from showing interest and kindness to Jewish refugees who arrived at our ports without a transit visa from our foreign representatives - if the British government allowed them to enter Palestine–. Various Jewish organizations, therefore, extended their gratitude and appreciation to our government.

In his book Türkiye’s Modernization: Refugees from Nazism and Atatürk’s Vision translated into Turkish, Arnold Reisman elucidates that Türkiye had admitted hundreds of Jewish scientists and artists since 1933, which also continued throughout the Second World War. The work discusses in detail that a large group of people from medical doctors to lawyers, architects and musicians found a safe living in Türkiye in those challenging years.

In the end, contrary to the general attitude in Europe and the Balkans, the Turkish Government was attentive to ensuring the security of our Jewish citizens and made efforts to prevent any harm to them during the years of the Second World War. No Turkish Jews were deported. Meanwhile, the decline of the Jewish population in Thessaloniki from 80,000 in 1939 to 5,000 in 1945 is thought-provoking. The tragic scene showing the Jews’ surrender to the Nazi occupation forces to be transferred to Auschwitz during the Holocaust calamity in Southern Macedonia was also striking.